Catastrophe and Calamity: Picturing British Disaster

Donna West Brett, Catastrophe and Calamity: Picturing British Disaster, Disaster Discourse Conference, University of Bucharest, June 2022.

H. Scott Orr, (1881-1972) The destruction of airship SL-11 near London Sep 1916. Gelatin silver prints | 13.4 x 8.3 cm (image) | RCIN 2503180. Royal Collection Trust, London.

The mutual development of modernity with the photographic medium in turn-of-the-century Britain intersected with events of anarchy, urban tragedies, natural and industrial disasters, conflict, and a global pandemic, avidly recorded by the media for public consumption. This paper considers the ways in which the visual record was used to report such disasters accompanied by a burgeoning media and visual culture by way of the illustrated news, postcards and stereo-views that were produced for public consumption and became active protagonists in the British propaganda campaign. Further it reflects on the changing aesthetics of disaster images driven by technological advancements, public desire, and media practice.

In this paper I will look at two examples of disaster photography, the first being the Fenian terrorist attack on the Clerkenwell Prison in 1867, and second, the destruction of a German airship, popularly referred to as a Zeppelin, over Cuffley, Essex in 1916, famously referred to as Zepp Sunday. Both incidences encompass attacks on Britain roughly 50 years apart and offer a means by which to trace the burgeoning public interest in visual culture as a mechanism for collective remembrance, political propaganda and spectacle. While the narration of other significant disasters such as the global 1918 Influenza Pandemic highlights the lack of contemporaneous commemoration and remembrance, the media and public response to these two events was substantial in their media coverage and in the dissemination of visual culture.

Clerkenwell Prison

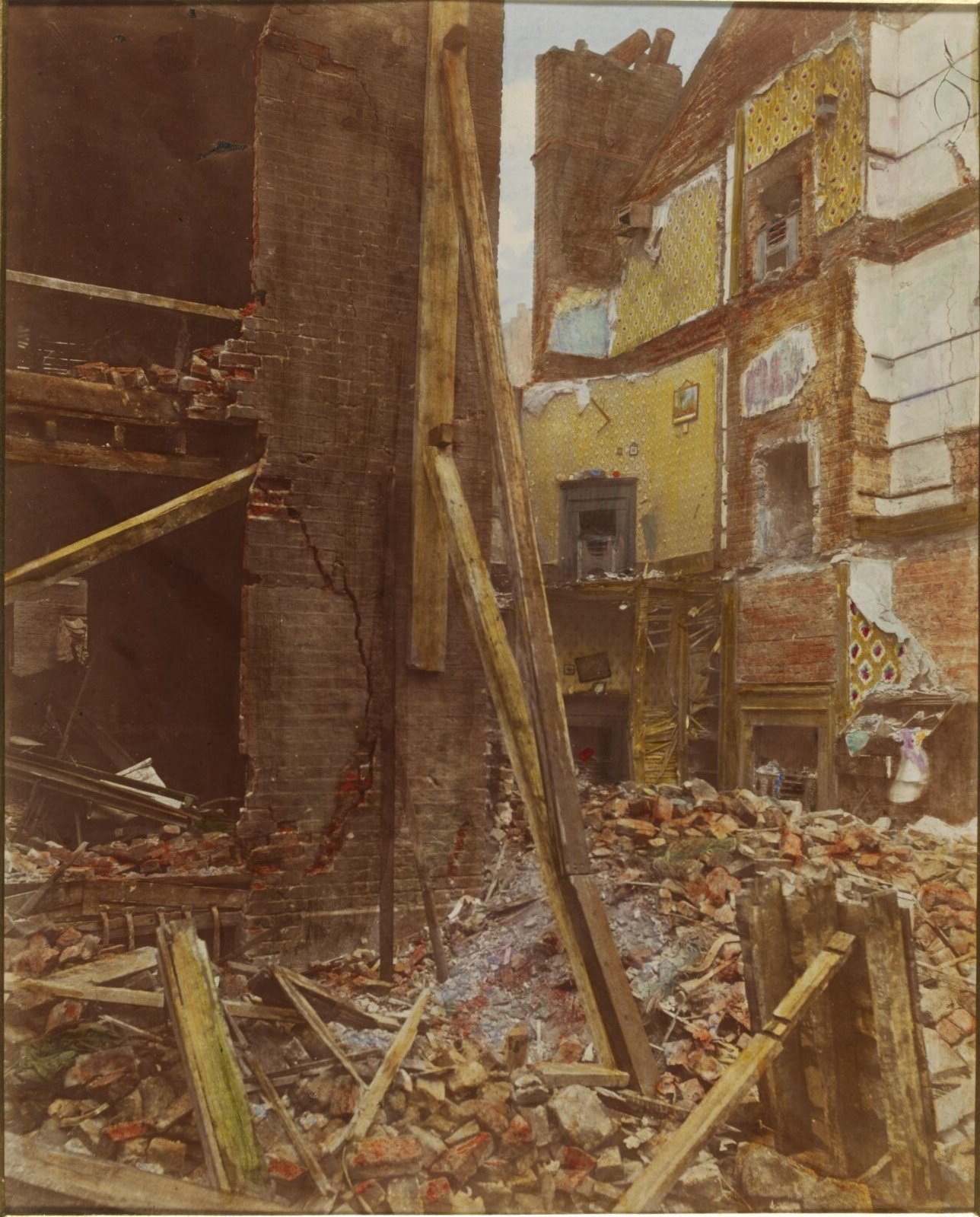

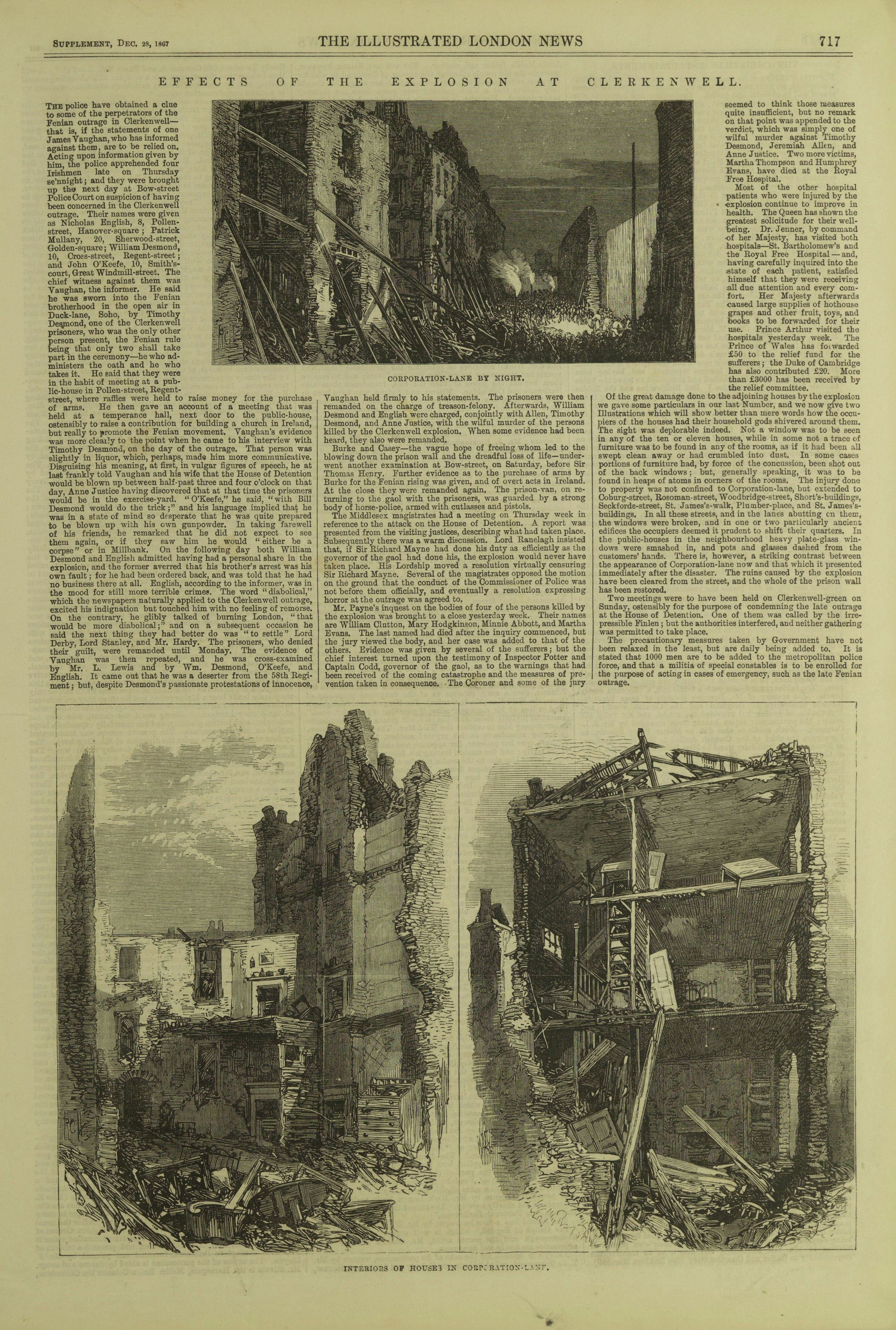

On 13 December 1867, Fenian (Irish Nationalist) sympathisers attempted to spring compatriot Captain Richard O’Sullivan Burke from the Clerkenwell Detention House in Islington, London. Burke had been arrested in Manchester along with TJ Kelly, Joseph Casey and associates for their part in a foiled Irish revolt around September that year. During their transfer to jail their van was ambushed and a Police Sergeant Charles Brett was shot. After his recapture, Burke was sent with Casey on remand to Clerkenwell. At 3.45 in the afternoon a massive explosion ripped the prison wall apart, the force of the blast demolishing a nearby row of houses in Corporation Lane. A reported ten locals were killed and over 100 injured although the accounts tend to differ across various media.[1] The architectural photographer, Henry Bedford Lemere, who had a studio on The Strand, lived only a mile or so from the prison in Albert Street. On hearing the explosion Lemere took his camera to the site and captured the aftermath of the terrorist attack, possibly with the aim of capitalising on the widespread interest in Fenian activity of the time. Several of these original 10 x 12-inch albumen prints are held in the Victoria and Albert Museum, with one hand-coloured version on display in 2019-2020 in the new photography galleries. The V&A also holds a number of Lemere’s architectural photographs, and one can see his interest in the built environment at play in these images albeit in renditions of buildings impacted by disaster.

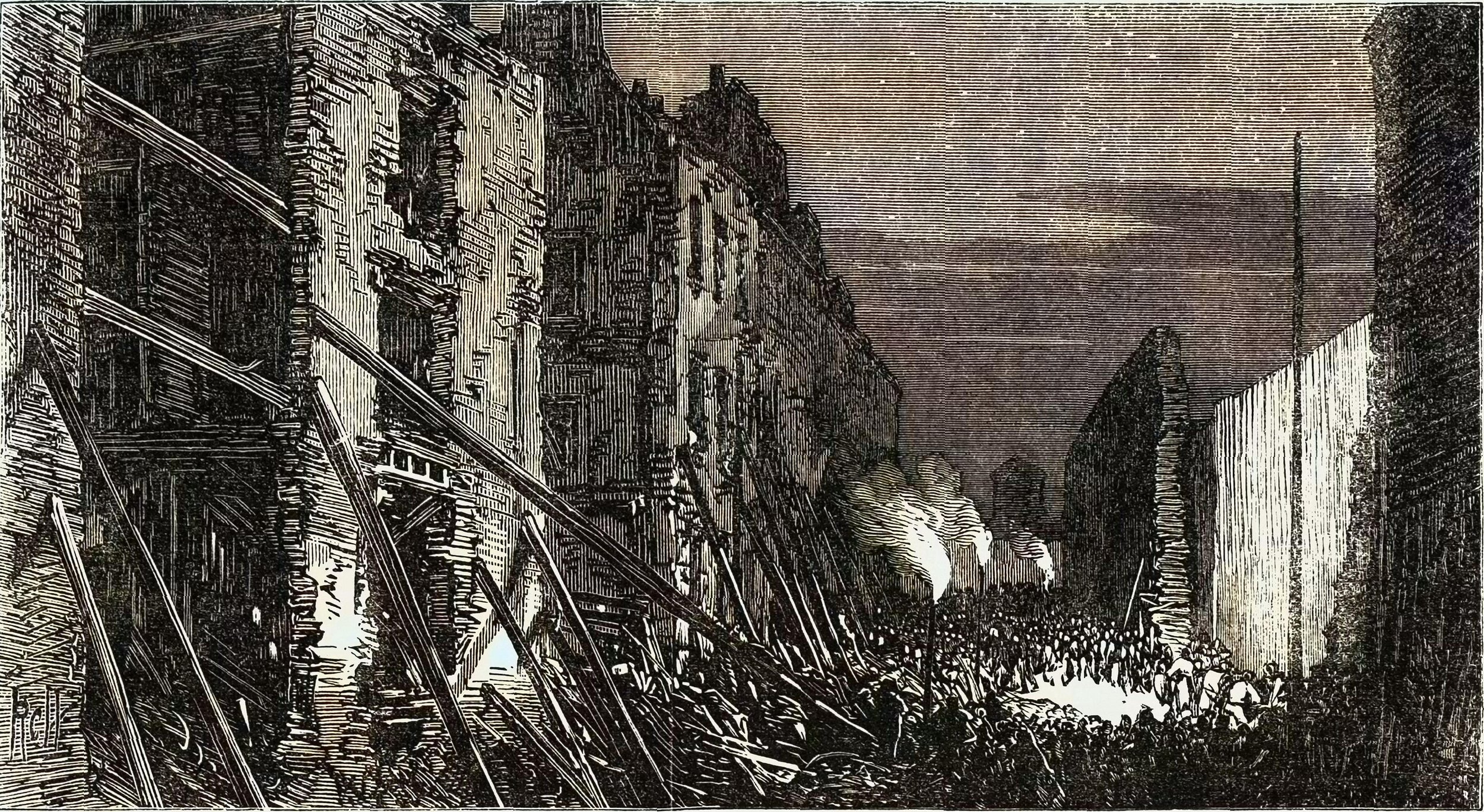

According to Anet Blackmore the photographs were first published as eight carte-de-vistes, entitled: 'Scene of the Fenian Outrage at Clerkenwell, 13th Dec. 1867'. On the back of these photographs are the emblems of both Bedford Lemere and Henry Hering, a well-established photographer who also operated as a print seller and publisher. I recently confirmed the location of these undigitised images held in a local history institute in Islington, London. What we do know is that Lemere’s photographs were seemingly used as the basis for engravings accompanying newspaper articles of this significant event, a common practice at the time. In the Illustrated London News article “Effects of the Explosion at Clerkenwell” the author writes, “we now give two Illustrations which will show better than mere words how the occupiers of the houses had their household gods shivered around them. The sight was deplorable indeed. Not a window was to be seen in any of the ten or eleven houses, while in some not a trace of furniture was to be found an any of the rooms, as if it had been all swept clean away or had crumbled into dust.”[2]

While the images in this article evoke the photographs by Lemere of destroyed houses, one in particular appears to have been drawn directly from one of Lemere’s photographs with some applied artistic license. In this reproduction the overall image has been cropped and visual obstructions have been removed or relocated providing the reader with an unobstructed view into the central area of the scene. It is here that a crowd of onlookers replace the policemen, lit by burning streetlights as day turns to night, drawing our attention to a central void. This illuminated scene brings to light the construction of a temporary wall enclosing the prison exercise yard from which Burke and Casey were meant to escape. Conspicuously absent from the Lemere photograph, the presence of the reconstructed wall in the engraving foregrounds the passing of time between the bombing and Lemere’s photograph on the 13th of December, and the construction of the wall as described in the article on the 28th. It seems that for some reason the two events of the bombing and the wall reconstruction were conflated in the news article engraving as if to give currency to the article itself as the ‘latest’ news from the scene. The destruction of the wall also features on the cover of Harper’s Weekly, in which the reader is situated in the position of the Policemen inside the prison exercise-yard looking out at the destruction.

The lead up to the Clerkenwell Outrage and its aftermath were splendidly illustrated in the press with detailed representations from the initial escape of Burke, the search and capture of the Fenian group members responsible for the bombing, and the ensuing trial. Each chapter played out across the press in text and image over the following year.

Zeppelin Disaster at Cuffley

While images of the Clerkenwell outrage were disseminated via the newspapers, and the set of cartes-des-visites, the Zeppelin disaster at Cuffley became what can only be thought of as a sensation.

On the night of 2 September 2016, over Cuffley, Hertfordshire, a German army Schutte-Lanz airship SL11 (often referred to as a Zeppelin) was shot down by 2nd Lieutenant William Leefe Robinson of the No. 39 (Home Defence) Squadron, who was flying a biplane from Suttons Farm. The airship commanded by Hauptmann Wilhelm Schramm with 15 crewmen was the first Zeppelin to be shot down by another aircraft over England bursting into flames and crashing in a field near the Plough Inn, but not before launching over twenty bombs on Edmonton, Penders End, Enfield Highway and other locations including the Crews Hill Gold Club.[3] The fiery descent could be seen for 60 miles and features in many accounts of the event across the region.[4]

For example, Muriel Dayrell-Browning, who was staying at the Strathmore Hotel in Tavistock Square, London recalled what she referred to as the ‘sight of my life’ in a letter to her mother. “At 2.30 I was awakened by a terrific explosion and was at the window in one bound when another deafening one shook the house. Nearly above us sailed a cigar of bright silver in the full glare of about 20 magnificent searchlights. A few lights roamed around trying to pick out his companion. Our guns made a deafening row and shells burst all around her. For some extraordinary reason she was dropping no bombs,” as Dayrell-Browning described in referring to the airship. “The night was absolutely still with a few splendid stars. It was a magnificent sight and the whole of London was looking on holding its breath.”[5]

Dayrell-Browning’s account of the attack included a description of the impact when “the flames tore up into the sky and then the thud and cheers thundered all around us from every direction. The plane lit up all London and was rose red. …They fell – a cone of blazing wreckage thousands of feet – watched by 8 million of their enemies. It was magnificent, the most thrilling scene imaginable.” [6]

The aircrash site drew tens of thousands of visitors the next morning to view the wreckage and collect souvenir trophies of twisted wire. On 5 September the Hobart Daily Post reported the rush of sightseers to Cuffley, so great their number that extra homeward trains were scheduled.[7] Motor buses from the neighbouring town conveyed troops to the area in order to control visitors as they also did on the occasion of another Zeppelin crash of early October at nearby Potters Bar. In this instance, an L31 airship commanded by Kapitanleutenant Heinrich Mathy was shot down at Potters Bar, Hertfordshire. While his crewmen were caught in the airship Mathy jumped from a great height but died minutes later. The following morning The Times journalist, Michael MacDonagh took the train to report on the scene. “The train I caught was packed,” he wrote. Despite the rain and a “thick, clammy mist,” joyful crowds had already gathered at the site two miles from the station. One body MacDonagh reported had been found some distance from the wreckage and on the ground he saw “the imprint of his body clearly defined in the stubbly grass.”[8] So popular was the destruction of Zeppelins, that photographs of the fated L32 Zeppelin at Billericay only two weeks before were produced as stereo views for the broader souvenir market, a 3D viewing experience that offered the feeling of being in the thick of the action. The Realistic Travels company, with offices in London, Capetown, Bombay, Melbourne and Toronto, profited from the unfortunate demise of the German airmen with this stereo view card no 67 picturing the charred bodies of the Zeppelin crew.

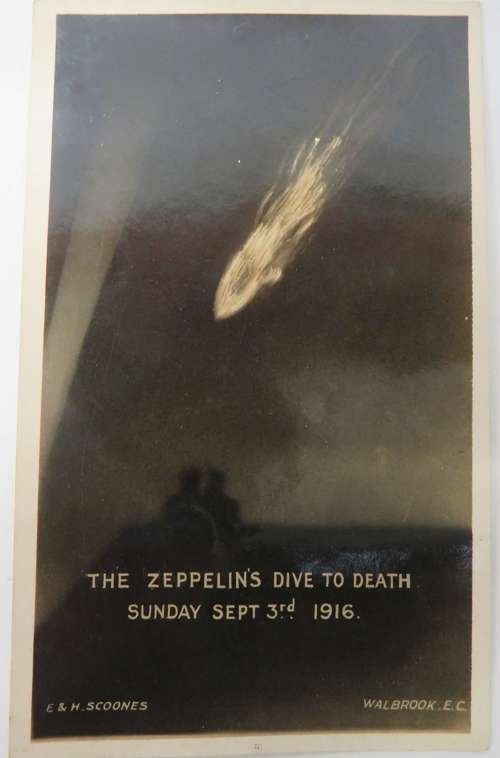

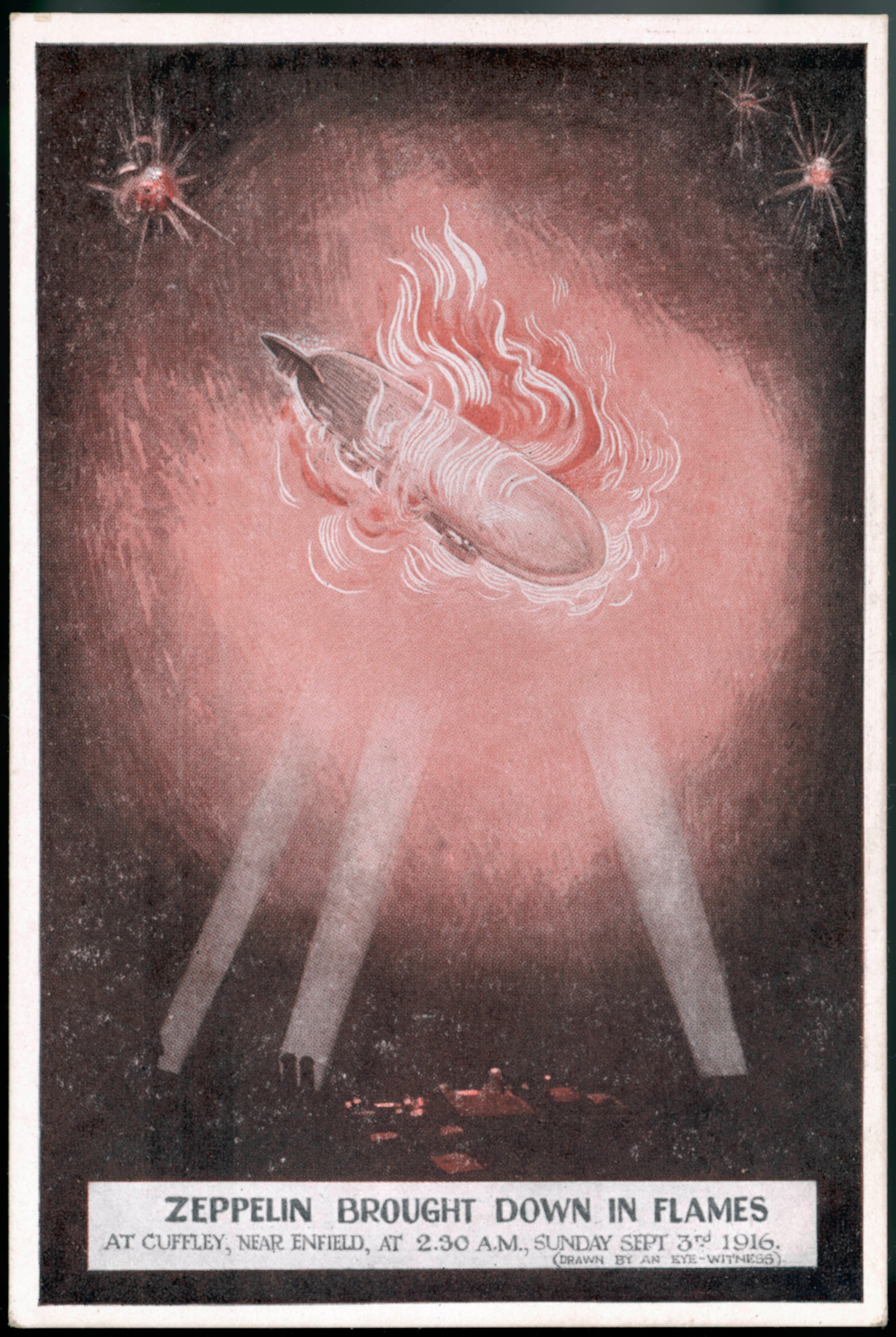

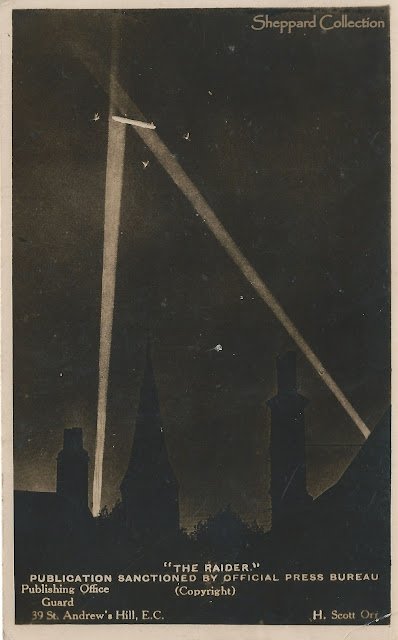

The Cuffley event, however, brought the madness of what was called ‘Zepp Sunday’, an event that was seared into public imagination and the media. Headlines such as “Lesson in-caution to the Baby-Killers,” “Zeppelin’s Last Gasp,” or “How the monster came down: scenes at the wreck,” from the Daily Sketch, are just a few that encompass the media coverage of the sensational event accompanied by the offer of 2000 pounds to bring one down. Newspaper articles featured drawings or photographs of the tumbling Zeppelins or scattered remnants at the crash site as a means by which they could rally civilian morale. The production and dissemination of postcards furthered this aim and were active protagonists in the British propaganda campaign to forge public pride and dampen German morale. As David Marks comments, “A remarkable resilience shines through in these postcards and, once the raiders had been overcome, their tone became triumphant with the pilots, who were responsible for the bringing down of ‘the Baby Killers’, becoming heroes in their own right.”[9] While the Zeppelin’s invention as a silent weapon formed an integral part of Germany’s wartime identity, it also did not disappoint as a psychological weapon, as Marks put it and similar German postcards reinforced the might of their airships. These images are in stark contrast to those included in newspaper reports of destroyed houses and lost lives such as those commonly published in the Daily Sketch or The Sphere.

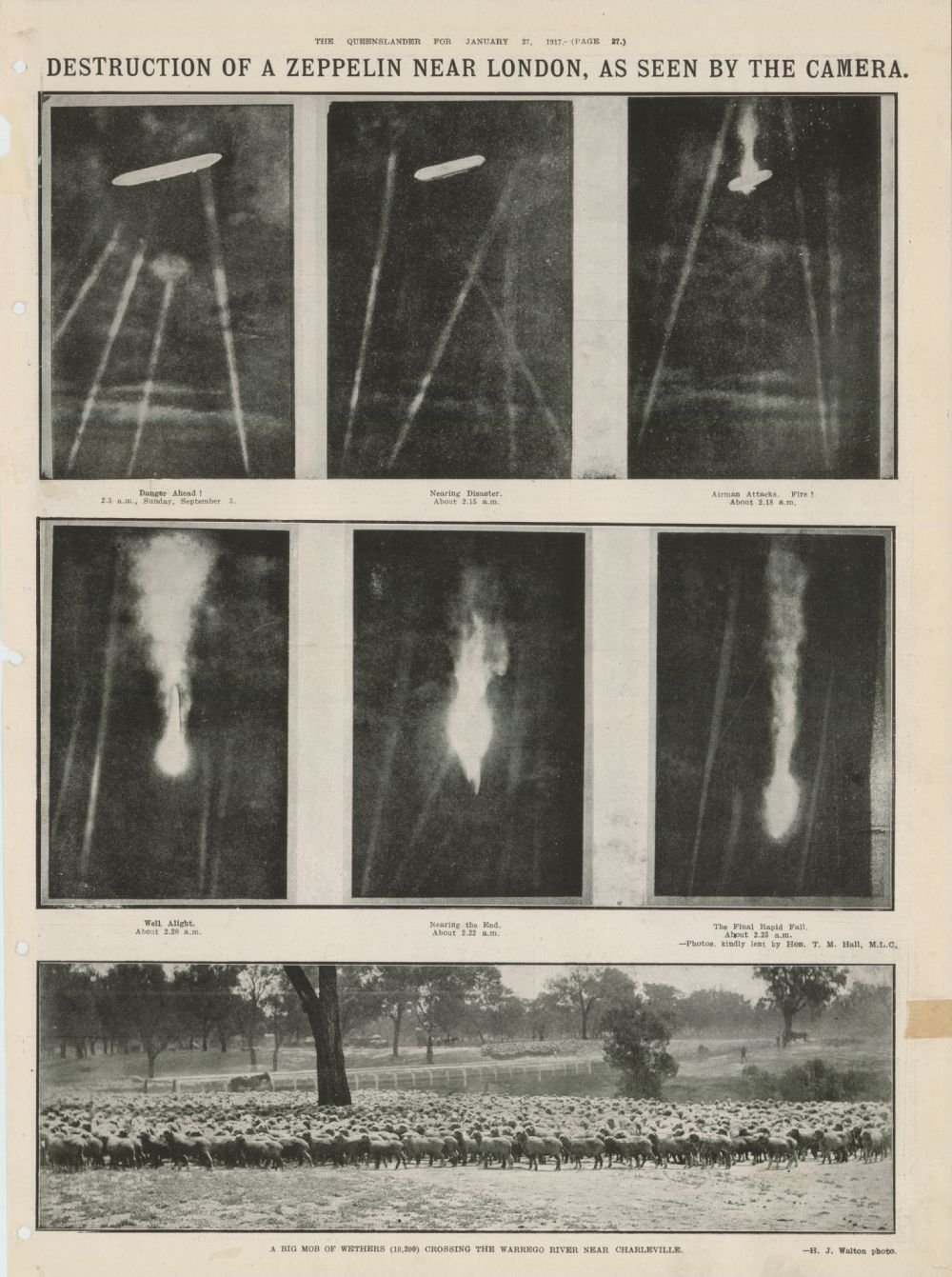

As the SL11 scoured the skies for targets on that September evening in 1916, photographer H. Scott Orr trained his camera toward the Zeppelin lit by searchlights from the ground. While many photographs were taken of the doomed Zeppelin that night, Orr captured the cigar-shaped vessel in six stages: from minutes prior to the impact of Robinson’s guns to the initial explosion of fire and subsequent collapse of the vessel as it plunged to the earth. Produced in a series of small gelatin silver prints, each position is colourised to coincide with the corresponding state of destruction, from black-and-white, to a blazing orange and finally an intense, vibrant red. Various editions of this photographic series are in the British Royal Collections, the Museum of Modern Art, the Getty, and the New Orleans Museum of Art, collected as works of art in their own right. The full series of six images found their way into The Queenslander newspaper, on the 27th of January 1917, in a picture spread titled “Destruction of a Zeppelin near London, As Seen by the Camera”, with the forms becoming even more abstracted in newsprint. Juxtaposed with a photograph of a big mob of over 10,000 Wethers crossing the Warrego River near Charleville, the images look bizarrely out of place in the Queensland press. While the photographer of the sheep mob is credited, those by Orr are not, instead the Hon. T M Hall MLC is credited as loaning the images to the newspaper. It is on closer inspection that one realises the reproductions are not from the original photographs, but rather those of a series of postcards sanctioned by the British Official Press Bureau. Collected by TM Hall, the reproductions indicate the geographically broad dissemination of this type of postcard depicting disasters and destruction from afar. The postcard typography across these six images brings home the perilous end of the Zeppelin heralding “Danger Ahead” at 2.15 am on Sunday September 3 to the “Final Rapid Fall” about 2.25am. The spectacle is here depicted for mass dissemination and consumption through the combination of dramatic images and descriptive text.

H. Scott Orr, (1881-1972) The destruction of airship SL-11 near London Sep 1916, 1-6 position

Scott Orr was not the only one to take photographs of the SL11 nor to be awakened by the spectacular event. Eleven-year-old Patrick Blundstone was awakened by a house servant called Poolman and on heading downstairs they could see “flashes and then heard ‘Bangs’ & ‘Pops’.” “Suddenly,” Patrick wrote in a letter to his father, “a bright yellow light appeared and died down again.” Right above the house was the Zepp which had broken in half and “was in flames, roaring, and crackling” according to Patrick. His account of this memorable event included graphic descriptions of the bodies likened to a roast dinner, and a rudimentary drawing of the family house, the Zepp and the path of the wreck downward as it fell toward the nearby field illustrated by directional arrows. Patrick’s enthusiastic account of the Zepp’s destruction highlights the power of the press and political propaganda in rallying the public in difficult times and it is not hard to imagine him purchasing the stereo view of the deceased German airmen as a souvenir of his adventure. The letter, which is in the Imperial War Museum collection, is accompanied by four postcards commemorating the Cuffley event.

Other accounts and renditions of the falling Zeppelin grace diaries, letters, newspaper reports, paintings, and illustrations with many reproduced as postcards, such as these lavishly drawn images by eyewitnesses and those sanctioned by the Official Press Bureau that formed an array of commemorative souvenirs. This included the illicit collection of ephemera such as disaster remnants and while the public were not officially allowed to take pieces of the airships themselves, under the Defence of the Realm Act, it was not uncommon to see citizens of all ages rummaging for pieces of history spread out over vast tracts of land. Building on this public fascination for such material the War Office gave the British Red Cross Society vast quantities of wire from the wreck to be made into brooches, bracelets, rings and cuff links which were sold for the benefit of the Society’s funds. Sanctioned postcards were also sold to raise money for families affected by the bombings and the wreckage was put on display in London.

This sense of spectacle in the face of destruction and disaster evokes the Coney Island exhibitions of the early twentieth century where visitors could face the thrill of the Fall of Pompei, the volcanic explosion of Mount Pelee on the hour, or the ‘Fire and Flames’ recreation of a real New York apartment fire. “In its very horror, disaster conferred a kind of meaning to its victims’ lives, transforming commonplace routine into the extraordinary,” as John Kasson put it in Amusing the Million.[10] Likewise the sensational scenes of disaster made their way into the melodrama of the stage or silent screen. As Bernard Beckerman proposes, “spectacle is often realised mainly in visual terms, the visual terms do not alone make the spectacle’, rather he says it exists “between extraordinary actuality and fascinating illusion,” here seen in the both the Clerkenwell Outrage and the Zeppelin disasters across the media and representations in popular visual culture. The visual representation’s temporal proximity to reality creates a physical and psychological response from the viewer, in that it takes them out of the humdrum of the everyday, and they have lived to tell the tale.[11]

The public’s appetite for disaster souvenirs such as postcards, stereo views and news images is matched only by the production of such material, or what Susan Buck-Morss suggests as a “promiscuity of images.”[12] Much like disaster tourism today, dramatic scenes such as these draw the public imagination, a phenomenon utilised in politically driven propaganda to bolster support for conflict. These illustrated newspaper articles, stereo views, photographs and postcards as material culture, represent not just a mediated experience of the disasters themselves, but forged connections between families, neighbours and strangers as narrative devices for collective witnessing and memory. These objects that were collected, touched and traded, both illicit and sanctioned, in turn act as material witness for spectacle and a means to picture British disaster for public dissemination.

DONNA WEST BRETT, 2022

[1] Bloom 2010, 241 and Anet Blackmore HISTORY OF PHOTOGRAPHY, VOLUME 13, NUMBER 4, OCTOBER.DECEMBER 1989, See London Illustrated News, 21 December 1867, p663

This is one of four 10 x 12" albumen prints of these views in the V&A collection, bequeathed to the Museum in October 1868 by Chauncey Hare Townshend, a major collector of early photographs in Britain. While they lack identification emblems, the close correspondence to the set of eight images suggests that Townshend's source was most probably Henry Hering, whose business was located only a few streets away from Bedford Lemere's at 137 Regent Street. This distribution relationship between Bedford Lemere and Hering also points to the probable source for many of the other photographs in the Townshend bequest, including works by Roger Fenton and seascapes by Le Gray, photographers Hering promoted, along with a range of architectural views, in his advertisements in the local press

[2] London Illustrated News, 28th December 1867

[3] Alan Simpson, Air Raids on South-West Essex in the Great War: Looking for Zeppelins at Leyton, Appendix D, Pen & Sword Books, 2015.

[4] Zeppelin Vs British Home Defence 1915–18 By Jon Guttman · 2018, 56

[5] The Baby Killers : German Air Raids on Britain in the First World War p 32

[6] The Baby Killers : German Air Raids on Britain in the First World War p 32

[7] Rush of Sightseers, Daily Post, Hobart, 5 September 1916, 5

[8] The Baby Killers : German Air Raids on Britain in the First World War p 38

[9] David Marks, The Zeppelin Offensive…. 15.

[10] Amusing the Million: Coney Island at the Turn of the Century By: John F. Kasson and https://ephemeralnewyork.wordpress.com/2015/09/14/coney-islands-obsession-with-disaster-and-death/

[11] Stagecraft, Spectacle, and Sensation. Cambridge companion to Melodrama, 127.

[12] Buck-Morss S (2004) Visual studies and global imagination. Papers of Surrealism 2: 1–29.